The opening

titles of Alfonso Cuarón’s newest film Gravity

warn that life in space is impossible. The rest of the film puts that

thesis to the test as rookie astronaut Ryan Stone (Sandra Bullock) and veteran

Matt Kowalski (George Clooney) struggle to survive as a relentless debris storm

destroys the space shuttle, and pretty much anything else in orbit capable of

supporting life. The plot is straight-forward and psychologically relentless as

one disaster after another challenges Stone’s ability and willingness to make

it safely to Earth. Cuarón’s Gravity triumphs

because of three strengths: its use of space as a setting, the performances of

Bullock and Clooney, and Cuarón’s directorial skill.

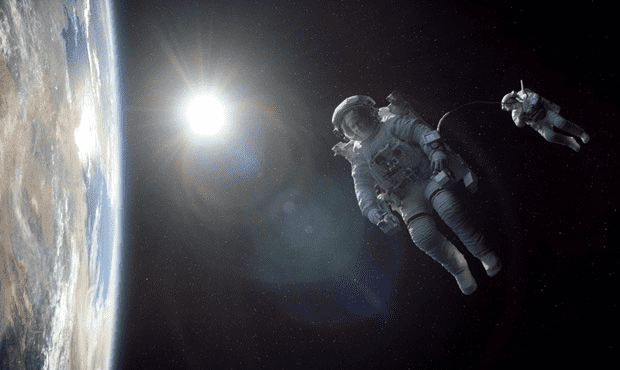

While outer

space serves as the setting for the film, Gravity

continually shifts the film’s focus between shots of Earth and vastness of

outer space and the cramped world that Stone inhabits. The opening of the film

consists of one extended shot—I’m not sure how long exactly, but it is long. Cuarón

lingers on the majesty and loneliness of space as the nervous Stone and the lame

humor of Kowalski flutter in and out of view.

After Stone becomes separated from the space shuttle, she drifts off

into space, spinning out of control and seemingly lost forever, until Kowalski

appears as a growing speck in the distance eventually reining in the wayward

astronaut. With these shifts, Gravity evokes

Kubrick’s 2001 in depicting the

wonder of outer space. Also, not since 2001

has space seemed so empty, vast, and cold.

|

| Bullock and Clooney, just hanging out. |

Bullock and

Clooney provide the star power necessary to carry such a straight-forward plot

that relies on the audience believing in these characters as people trying to

survive in extraordinary circumstances. Clooney carries himself with charm,

annoying confidence, and the wisdom of a seasoned veteran (astronaut or actor,

it doesn’t really matter). His droll stories and repetition of ordinarily

mundane dialogue grows more meaningful with each utterance. His instance that

he “has a bad feeling about this mission” becomes more poignant with each

rendering. Clooney conveys Kowalski’s confidence and experience with ease and

offers a strong counterpoint to Stone’s anxious competence. In Gravity, Bullock gives the performance

of her career. Actors rarely win Oscars for their performance (The Blind Side is only bearable because

of her, the rest of the film is the worst kind of liberal paternalism that

passes as a story of African-American uplift), but Bullock deserves it here.

She expertly balances Stone’s abilities and apprehensions. Her physical acting

skill shines through in the few scenes outside of her space suit. When Stone

seemingly reaches safety inside the International Space Station, she curls up

into a fetal position in one of the film’s most beautiful visual moments. Her

movement is natural considering her circumstances. Bullock performs the act

with a startling compactness. Her body moves with purpose and without waste. It

is a simple movement, practiced and executed to perfection, and it embodies the

greatness of Gravity.

Cuarón works

rarely and chooses his projects carefully. His last film, Children of Men, portrays a dystopian film where humanity has lost

the ability to reproduce. Never has the future seemed so irreversibly dead. Cuarón’s

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban remains

the best of the Harry Potter films. He treats the magic of the Potter universe

with respect and captures the growing maturity and sense of impending danger of

its characters. He waited until the 3D technology pioneered by James Cameron in

Avatar before attempting to make this

film. He wisely ignored the advice of studios who wanted to include a countdown

clock, flashbacks, and views of a rescue mission. Cuarón kept the focus where

it needed to be, on one woman’s awe-inducing journey of survival. In doing so,

he offered movie audiences a stunning mediation on grasping life from the jaws

of death.

No comments:

Post a Comment