The Fish that Ate

the Whale: The Life and Times of America’s Banana King

In

1910, Sam “the Banana Man” Zemurray, head of Cuyamel Fruit Company,

orchestrated a coup against the government of Honduran president Miguel Dávila.

Zemurray provided guns, money, and a former US naval warship to former

president Manuel Bonilla. The Cuyamel Fruit Company owned plantations in

Honduras and shipped bananas to the United States on its own fleet of ships. Success

in the volatile banana business relied on bribes and kickbacks to the Honduran

government, keeping the cost of business low and the profit margins high. When

the United States agreed to a treaty with President Dávila to administer

Honduras’s staggering national debt, Zemurray’s business was in danger. With

the J.P. Morgan Company’s agents assigned to Honduran customs houses collecting

taxes on Cuyamel exports, Zemurray would be taxed out of business. Secretary of

State Philander Knox warned Zemurray not to interfere in Honduras, but Zemurray

proceeded with the coup anyway. When Bonilla came to power, he voided the deal

with the U.S., protected Zemurray’s interests, and allowed Honduras’s crippling

debt to continually plague the nation.

|

| The house that Bananas built--it now belongs to Tulane. |

Richard

Cohen begins his lively biography of Zemurray with this anecdote highlighting

the extent that Zemurray, an immigrant from present day Moldavia, would go to

protect his business and his own interests. Cohen emphasizes how Zemurray’s

meteoric rise from impoverished immigrant to the “Banana Man” embodies the

equally inspiring and dispiriting nature of the American dream. Zemurray began

his career by seizing upon the untapped potential in the banana market: ripe

bananas. In the last quarter of the 19th century, importers

discarded ripe bananas because they would turn bad before they could reach

distant markets. Zemurray bought up the ripe bananas, arranged a delivery deal

with a local railroad, and made a fortune. Zemurray soon bought banana

plantations, banana boats, and anything and everything related to the

production of bananas. Making himself into a banana mogul required payoffs to

local governments, buying land from natives on the cheap, and other morally

ambiguous behaviors endemic to capitalistic enterprise In 1930, Zemurray sold

Cuyamel to United Fruit Company. Several years later, Zemurray orchestrated

another coup, this time to seize control of United Fruit. He saved it from the

disastrous management that nearly ruined the company during the Great Depression.

Zemurray succeeded in turning United Fruit around. In 1961, Zemurray died a

rich man with a troubled legacy.

|

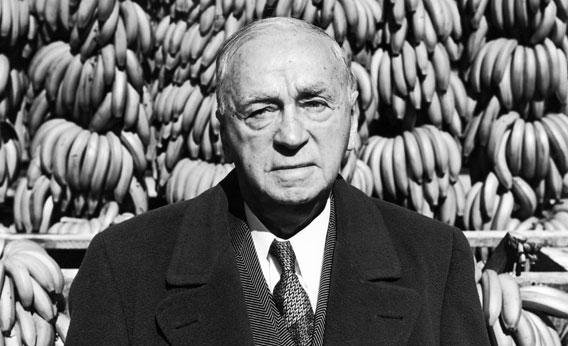

| Sam the Banana Man |

Cohen’s

book has two great strengths. The first is the fascinating life story of

Zemurray with his impoverished roots, his rise, and his moral compromises

necessary to stay on top, and his later in life devotion to philanthropy.

Second, Cohen’s energetic and sarcastic prose makes for an enjoyable read. The

first sentence of the book sets the tone for the rest, “Sam Zemurray spoke with

no accent, except when he swore, which was all the time” (3). At 242 pages,

with some padding*, the book reads quickly. I finished it in a few hours of

reading. Cohen also offers his own thoughts and insights into Zemurray’s life,

recalling his own efforts to grow a banana in Connecticut, his attempts to imagine

and understand the banana plantations of Central America, and a hilarious

footnote about a New Orleans policeman refusing to take Cohen into the

Iberville Projects, “’cause the sun is going down and I love my kids” (245). He

also enlightens the reader on the emergence of the banana into the American

marketplace in the late 19th century and how the foreign fruit

(Cohen argues that the banana is in fact a berry) became a quintessential

staple of the American diet. He also provides insight into the different types

of bananas and their unique features. In any specific type of banana, all of

the bananas are clones of each other—making them uniform but also susceptible

to disease. Zemurray made his fortune

importing the Big Mike banana, a type that died out in the 1960s. Today’s

bananas are of the Cavendish variety and those will soon go extinct as well.

The book takes a few diversions into the history of United Fruit’s activities

in the 1950s and Zemurray fades into the background. This shift of focus leaves

the responsibility that Zemurray had for the CIA’s or United Fruit’s activities

in Central America in the 1950s unclear. He also makes several factual errors

about the early history of the CIA that I was only aware of because I just read

a biography of the founder of the Office of Strategic Services.**

Overall

Cohen’s book succeeds as an entertaining and educating sread.

*most

notably skipping a whole page before starting a new chapter

** He

incorrectly states that the OSS was not dissolved at the end of World War II.

It was. The CIA was not created until 1947. Secondly he identifies Walter

Bedell “Beetle” Smith and Allen Dulles as the 1st and 2nd

Directors of Central Intelligence, they were the 4th and 5th.

No comments:

Post a Comment