The French, Spanish, German,

Haitian, West African, Caribbean, Vietnamese, and other ethnic groups that have

settled Louisiana in the past three hundred plus years have fused together to

create cultural traditions unique to Louisiana. In the past we’ve covered Mardi

Gras, the history of king cakes, the Natchitoches meat pie, and crawfish boils.

In honor of the Christmas season, we’d like to introduce another Louisiana

tradition: Christmas Eve bonfires.

|

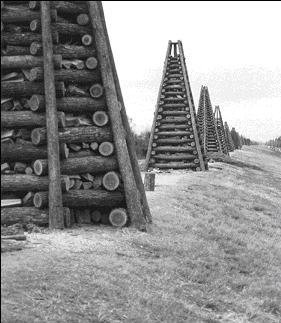

| The bonfires in their full glory |

On Christmas Eve, and more generally

in the month of December, residents of Louisiana who live along the Mississippi

river, especially between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, construct bonfires on

the earthen levees that surround the river. These levees protect the surrounding

areas from flood waters. These areas of high ground also make them prime

locations for the construction of bonfires. Tradition holds that the bonfires

are intended to help Santa Claus—or as the Cajuns call him Papa Noel, because

of course the Cajuns have their own name—find his way to the homes of residents

of Southern Louisiana. Louisianans construct wooden pyramid like structures,

with smaller support logs that give them the appearance of fences. This is the

typical appearance for one of these structures, but over the years people have

become more artistic in their creations. Many pay homage to Louisiana’s

culture, taking the shape of famous plantation homes, paddleboats, or even the

ubiquitous crawfish. St. James Parish, located about 30-40 miles upriver from

New Orleans, has the heaviest concentration of bonfires, especially in the

towns of Gramercy, Lutcher, and Paulina. Lutcher even hosts the annual Festival

of the Bonfires at Lutcher Recreational Park where they feature live

entertainment, food, local crafts, and of course, bonfires.

The origins of the Christmas Eve

bonfires are not entirely clear. French and German immigrants settled in St.

James Parish in the early 18th century. One theory holds that these

settlers continued European traditions of holding bonfires on or around the

winter and summer solstices after they established themselves in Louisiana. These

original pagan practices were incorporated into Christian beliefs as a way of

smoothing the way for conversion. The historical record, however, does not

support the claim of a widespread practice of bonfires until the 1920s and

1930s. Groups of young men formed bonfire clubs, where they cut down trees,

stripped them of their branches, and dragged them to the levees. After

constructing the pyramid-like structures, people filled with rubber tires and

other flammable materials. After World War 2, the bonfires grew in popularity

due to the development of St. James and the surrounding river parishes. And in

a rare victory for environmentalism in Louisiana, local governments banned the

burning of rubber tires and other toxins—recognizing that they were bad for

people’s health. Now these events serve as important cultural and communal

events. As with many of Louisiana’s great traditions, they provide an

opportunity to listen to music, eat delicious food, and for people to come

together as a community and celebrate the holiday season.

|

| Of course there's a Saints one |

The tradition of Christmas Eve

bonfires reflects the unique cultural forces that have shaped Louisiana’s

colorful history.